The New Normal

Big Tech and the emergence of internet-era aggregators and platforms require a fundamental rethink in how we structure an investment portfolio. We are in the early stages of this fundamental rethink, which has caused shares of the most successful aggregators and platforms, i.e., Big Tech, to be continually undervalued, although they are the most well-researched stocks. This systemic undervaluation will likely persist and only gradually reduce over time as these companies mature and investors better understand this new market landscape. The current supply-demand imbalance of Big Tech shares provides a significant opportunity for unconstrained investors (i.e., retail and HNWIs) to buy these companies at a deep discount today.

A portfolio compatible with this new reality should be more concentrated with a larger maximum position size. Many foundational practices of how investors structure a portfolio today were primarily built on data and realities of the pre-internet world where internet-enabled aggregators and platforms did not yet exist. For example, the SEC rule that places a “soft” cap of 5% on the maximum position size for diversified mutual funds came out in 1940, while Modern Portfolio Theory was introduced in 1952. The corporate competitive landscape back then was also more intense (i.e., fewer winner-takes-most outcomes), and without the internet, the largest companies in a given industry weren’t able to aggregate demand to the same extent current aggregators are able to.

To elaborate on this point, in the internet era, the companies who become dominant aggregators or platforms have vastly different competitive risk profiles than the industry leaders of the pre-internet era. Even when there is more than one successful aggregator in an industry (e.g., retail, VOD), they don’t always directly compete head-on but rather offer complementary products and/or focus on fulfilling different demand types (e.g., Netflix and Disney+). As a result, the concentration risk is not nearly as high as history would suggest when taking a large position in a winning aggregator/platform due to this now altered competitive reality. For these dominant companies, valuation risk is often more considerable than company-specific risk. However, the relative and absolute valuation risk for Big Tech is currently quite low.

Increasingly, the market is moving toward having fewer, larger and more durable quality companies, so how one structures their portfolio should take that reality into account. For example, the advertising market evolved from thousands of then “wide-moat” TV stations, radio stations, and newspapers globally to now with over half of the demand aggregated by Google, Facebook, and Amazon alone. The internet generally shifts demand from companies operating in the “middle of the pack” to a few truly scaled winners. One should not be underexposed to these winners, especially at their current valuations, simply because of historical rules or theories created decades ago. The more diversified portfolios which underweight Big Tech may in fact have inferior risk-reward profiles.

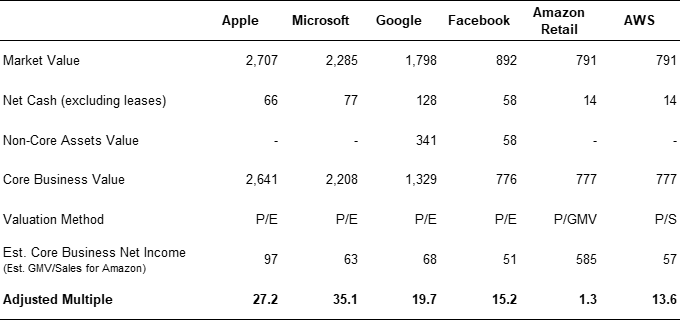

Google, Facebook, and Regulation

Google and Facebook are trading at 20 and 15 times their core business earnings today. We arrive at these figures by assigning a conservative valuation for their non-core businesses, removing the non-core operating losses, and subtracting the cash on the balance sheet. Doing so makes them more comparable to most other publicly listed companies. Google’s sales have grown 23% and profit 25% per year over the past five years and will likely see at least a low-teens growth rate over the next five years. Facebook has grown even faster and will likely see at least a low-teen growth rate over the same period. However, Facebook is priced around the same level as tech names like IBM and eBay. Both Google and Facebook, interestingly, are priced well below household consumer names like Coke, P&G, and McDonald’s despite their relatively stronger growth potential. The chart below shows the extent of their undervaluation when compared against other high-quality companies.

The most common threat cited for Big Tech is regulatory risk. However, the current valuation discount does not justify the likely true risk. The internet ushered in a new paradigm that allowed for the creation of dominant aggregators and platforms where demand flows to the largest operator(s) who can best leverage their initial demand to attract ever more incremental demand. Regulators can indeed break up these companies though the aforementioned fact remains. More specifically, that in the fullness of time and across a number of verticals, one player will still ultimately aggregate most of the market demand within an increasingly digitally driven world. Even in the face of a more restrictive regulatory environment, there are many ways to create ongoing shareholder value among Big Tech. Regulatory intervention may force them to abandon their best option(s), but their second-best option(s) is not often significantly worse, all things considered (e.g., Google’s reaction to the EU regulation eliminating the ability for the Android OS to default to Google search). Additionally, with the exception of Apple, Big Tech does not seem to exercise the full extent of their power, and instead voluntarily holds back in an attempt to (minimally in some cases) appease regulators. In short, regulation would likely cause Big Tech’s earnings growth to slow somewhat, but it likely won’t materially alter their overall business prospects.

Non-fundamental, systemic reasons can much better explain the undervaluation of Big Tech versus any fundamental rationales. Briefly, the former include:

Section 5(b)(1) of the Investment Company Act of 1940

Existing incentives of the investment management industry

The availability of growth investment dollars

Over-diversification

We’ll expound on each point in the following paragraphs.

The 5% Rule

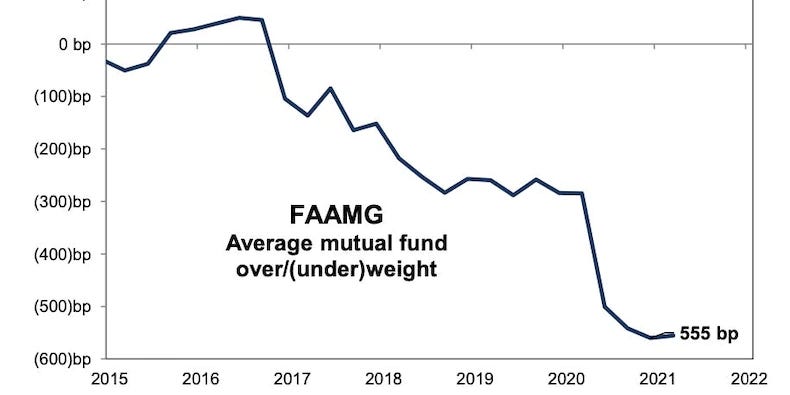

The Investment Company Act of 1940 puts a 5% “soft” cap on the largest positions a fund can hold for those who seek to market themselves as a “diversified fund”. It is a “soft” cap as there are exemptions: 1) 25% of the portfolio is exempted from this rule; and 2) when over the limit, the fund can continue to hold but cannot add to the positions. Because most mutual funds are marketed as diversified funds, it is increasingly difficult for them to overweight Big Tech without breaking this rule. This is especially true for growth-oriented funds, who traditionally make up a significant portion of the shareholder base of Big Tech. These funds have to manage their Big Tech exposure more aggressively and have been large net sellers of Big Tech shares over time. This contributes to the aforementioned share supply-demand imbalance. And while there are funds who successfully gain permission from their shareholders to drop the “diversified fund” requirement, many often don’t take that path.

Incentives in the Investment Management Industry

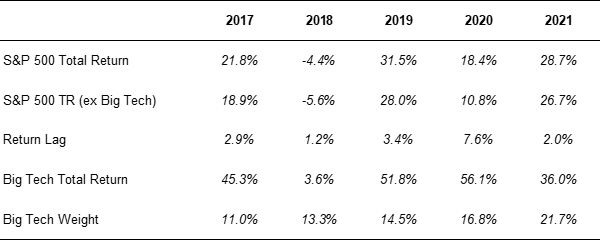

Even if the rule above were to be adjusted higher, active managers would still need to justify their fees. Generally speaking, active managers need to find “hidden gems”, non-consensus ideas, or things of that nature that produce excess returns. Buying Big Tech is the opposite of non-consensus. As such, it is very difficult to raise funds from institutional investors if much of the fund’s portfolio is predominantly comprised of very well-understood companies like Big Tech. This demand from institutional investors is arguably inconsistent with the reality in the market today and may, in fact, hurt a fund’s overall return. Active managers are given the difficult task of having to: 1) underweight the most undervalued shares; 2) choose to overweight shares from a group of companies that, as a whole, underperforms the market in every one of the last 5 years (see table below); and 3) beat the market return after layering fees on top. To date, very few active funds have shifted to become overweight Big Tech. Even the ones that do so, often don’t do so by a significant margin. The consistently lower than “normal” demand for Big Tech shares among active funds subsequently causes Big Tech to be consistently undervalued.

Over time, the rise of aggregator and platform companies would be quite disruptive to active equity managers. The active investment sub-industry is built on the idea that value can be added by finding inefficiently priced shares among the broader market of publicly listed equity securities. While we only have five “Big Tech” companies today, we are certain to have many more in the future. A growing percentage of the aggregate market cap of all publicly listed companies is shifting toward these few dominant, very well researched and understood companies. The businesses in the middle of Ben Thompson’s smiling curve, where above-average stock pickers can most differentiate themselves, are hollowing out. To be sure, there are many industries that won’t see the disruptive shift brought about by the likes of Big Tech. Even still, much of the incremental, aggregate profit dollars and market cap across the universe of listed companies is going to accrue to these aggregators and platforms, making them an ever-larger percentage of the overall stock market index. The burden of underweighting these companies should only increase moving forward. For managers that must underweight them, it is akin to playing on a “hard mode”, which only gets harder every year.

The Availability of Growth Dollars

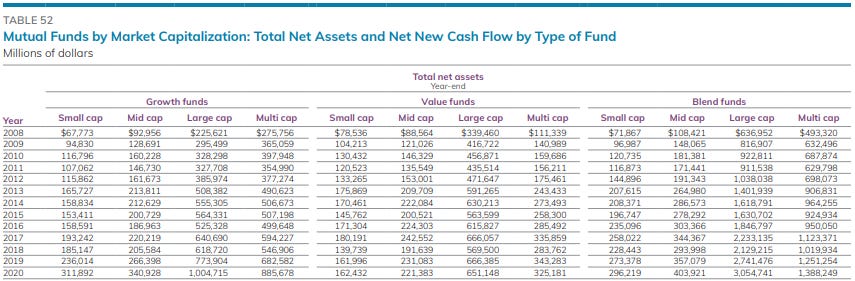

The overall allocation of investment funds to public growth equity is roughly 30% of the market, as shown in the table below. In the pre-internet world, companies reached maturity at a lower revenue base, and therefore behaved like a mature company at far smaller scale than today’s technology giants. But for Big Tech, and especially the less mature ones (e.g., Amazon, Google, and Facebook), they continue to behave more like typical growth companies today. The issue, however, is that there aren’t enough incremental growth investment dollars in the market today to cause the upward movement in Big Tech shares to be at the same rate as their fundamental growth. So, as Big Tech’s profitability grows, they find it harder to attract incremental demand for their shares, which must come from primarily non-growth investors, who make up the other 70% of the market of investment dollars. Big Tech’s heavy investments in growth, coupled with their lack of dividends, hurts their prospects among non-growth investors. Particularly as growth investors move to invest more into less mature companies in addition to non-growth investors' reluctance to over-index to Big Tech, Big Tech experiences the previously cited “abnormal” demand for their shares, which subsequently drives their systemic undervaluation. Big Tech has simply outgrown the availability of growth investment dollars.

Over-diversification

Most investors’ discomfort with concentrating their portfolio among their largest positions may be the most significant contributor to the undervaluation of Big Tech. It is easy to point to history and related studies of the past to justify why one should be diversified, especially after the GFC and the dot-com bubble. Sometimes, a position is trimmed when it gets too large, regardless of the fundamentals. As discussed earlier in this article, the growing concentration of aggregate corporate profits among a smaller number of internet-enabled companies is the new norm - a new norm which continues to be quite foreign for most investors. Warren Buffett, who faces none of the constraints mentioned earlier, presently has over 40% of Berkshire’s public equity portfolio invested into Apple alone. Ultimately, high concentration may never be a preferred reality for every investor though it’s appeal should broaden as investors’ understanding and appreciation of its merits, as applied to Big Tech, grows deeper.

Supply-Demand Dynamics

Given how market participants currently behave, a significant portion of the future demand for Big Tech shares may come from retail investors. This cohort of investment dollars is increasingly going to skew more conservative. Nonetheless, the incremental retail demand will come from two sources: 1) those who already own Big Tech and seek to buy more; and 2) those who don’t currently own it. For people in the first group, it is probably already their largest position even if they just market weight Big Tech. So while the comfort of how much they will let their largest positions run will probably improve over time, it will likely move slower than the pace of fundamental growth of Big Tech. The second group is mainly conservative investors who don’t traditionally invest in growth shares. It is the incremental demand from this group that may help fuel the demand in the years ahead.

The more matured Big Tech is less undervalued compared to the less matured Big Tech because they have broader appeal, more specifically stronger appeal to the more conservative investors who hold a lot of the incremental demand. Microsoft and Apple are on the more mature/less undervalued side, while Amazon and Facebook are on the less mature/more undervalued side, and Google is somewhere in the middle. Things that help broaden the appeal of the shares include:

Capital efficiency

Stable and increasing earnings

Dividends

Price per share

The volatility of core business

Limited capital committed to moonshots investments

Further, a company can improve its systemic undervaluation by engaging in stock buybacks. After a certain period of time, buybacks help the portion of the shareholder base that’s the most pessimistic about the company’s future to exit their positions and can help absorb supply from those needing to sell for non-fundamental reasons (e.g., portfolio weight). This helps improve supply-demand imbalances and create a longer-term positive impact on the share price. The positive impact that buybacks create for Big Tech is more than average company buyback as the shares are systemically undervalued and continue to be undervalued even after the buyback starts. This helps generate significant shareholder value as Apple’s buyback program has demonstrated.

Amazon

Amazon most clearly exemplifies the above mentioned supply-demand imbalance of a company’s shares. On the demand side, Amazon does little to appeal to more conservative investors:

Current accounting earnings are small compared to the company’s true earnings potential, which, in conservative investor’s mind, casts doubt on the ultimate degree of long-term profit potential.

The earnings are also quite volatile by the Big Tech standards.

Amazon continues to invest heavily in its core business as well as various moonshots.

The company provides zero financial or other disclosures regarding its moonshots investments.

Amazon pays no dividend.

On the supply side, it is the only Big Tech company that doesn’t engage in buybacks today and does not benefit from the abovementioned impact. Further:

Amazon has a relatively low cap on the cash portion of their typical employee compensation package, which encourages a greater incremental supply of shares to be added to the market as employees sell down their vested shares

Jeff Bezos and Mackenzie Scott together add more supply of shares into the market than other Big Tech founders.

This large imbalance likely makes Amazon the most undervalued Big Tech company today. AWS, for example, trades at a similar P/S multiple to the already undervalued Microsoft despite much greater growth potential and margin upside. Amazon exemplifies how a $1T+ company’s growth mindset, which most certainly creates longer-term shareholder value, can indeed harm its medium-term valuation. Nonetheless, the business will eventually move up the maturity curve, and the company will behave more like a mature company, bringing the twin benefits of margin and valuation gap improvements to longer-term investors.

Disclosure: both myself personally and ESA Global Value fund are long Amazon, Google, and Facebook

Credits: Will Schoeberlein and Pete Pasurapanya for proofreading and editing this write-up

This is a brilliant analysis. I never imagined the lack of investment dollars to be an issue.

Thank you for the analysis krub!